A Nightmare of Our Own Making: Crafting Ecological Themes In Our Writing

Recent lecture given to San Luis Obispo writing group

Hi everyone. Thought I would post the lecture I gave last night in its entirety (see below). This includes additions I didn’t share because of time constraints.

Couple of things first. I was interviewed by the wonderful folks at Jackson County Library. We talk everything from Ten Sleep to Mexican cowboys, to monsters, and me once visiting the dusty artifacts beneath the Beale Memorial Library. Please watch and share. Only takes a few minutes of your time and the filmmaking is really cool.

I also wrote a hard-hitting piece for CrimeReads, “Re-imagining the American West for Modern Horror Audiences.” Here’s an excerpt:

We live in precarious, uncertain times—on the edge of a knife you could say. Horror writers willing to hold a mirror up to society need to pay close attention. Some of this is happening in the American West. Gun barrels have been aimed at everyday citizens standing against legalized human trafficking. And many detainees have been sent to faraway detention centers in jungles that few Americans have ever seen. Feels like we’re one trigger-happy officer or suicide bomber away from the U.S. military firing on its own civilians. I’m terrified of this real-life horror story playing out, because we know to what lows American soldiers have stooped in past wars, whether it’s an atrocity that famed war writer Tim O’Brien witnessed during the Vietnam War, or those war crimes buried in the war rubble of Afghanistan and Iraq. The real-world angry political rhetoric is there—Angelenos likened to savages in need of imprisonment and removal—all too reminiscent of the bloodied history of the American West that left lands ravaged and millions of Indians removed, buried, homeless, stateless, starved, and forgotten. However difficult to stomach, these types of connections are fodder for the horror writer willing to hold that mirror and spin tales of wights, vampires and mysterious will-o’-the-wisps with dark, just intentions.

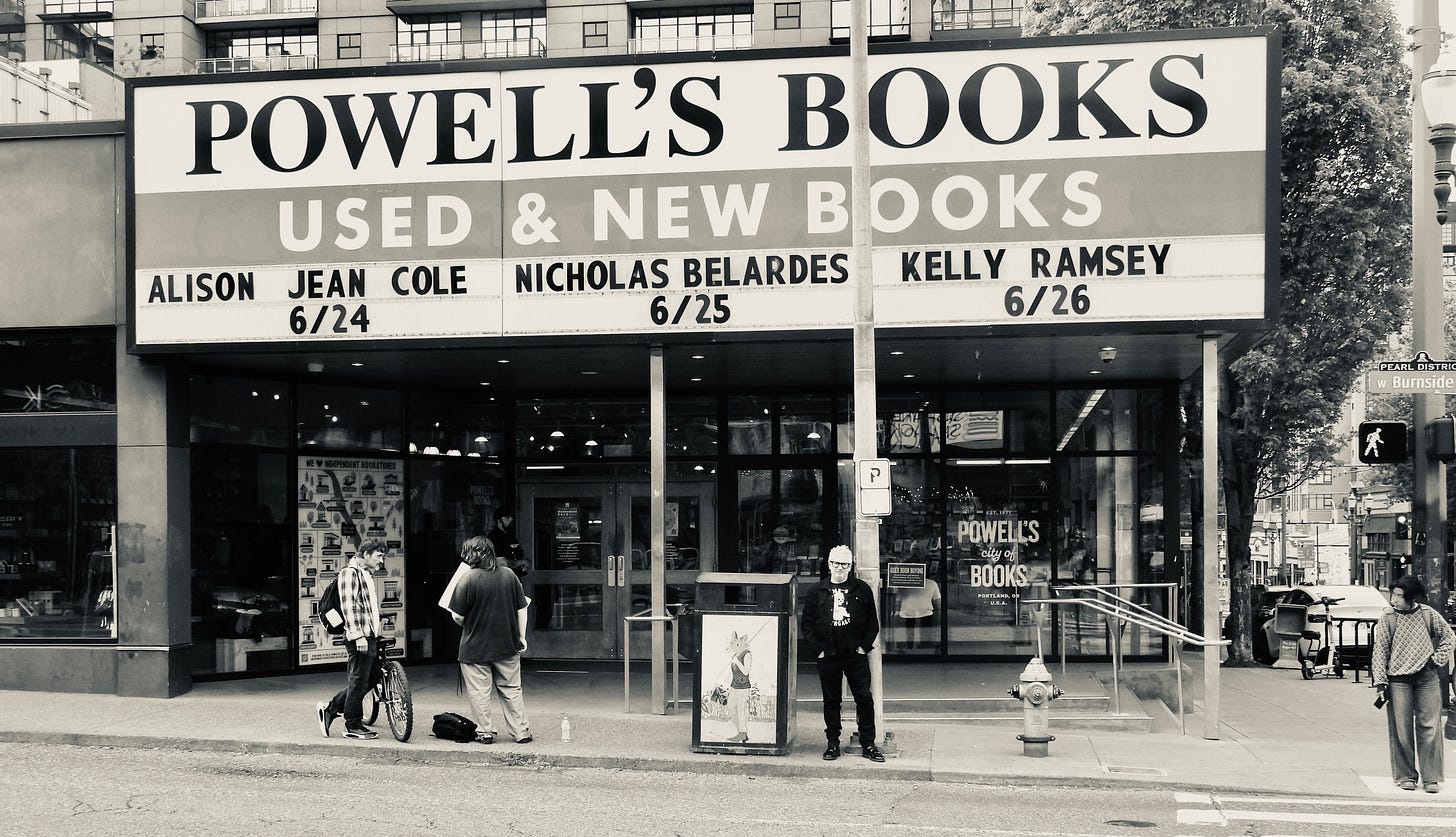

Ten Sleep launched at Powell’s City of Books! I have to show a few pics of my name on the marquee, which was a huge surprise!

My July 8 evening lecture at SLO Nightwriters. Mostly as is. Sorry for any typos:

I’m here to talk about writing that sells. I know, we have a themed topic on eco-horror. But I think it’s important you know—I don’t write anything that I’m not aiming to sell. I may fail, but that’s always the goal.

There are so many ways to go about crafting novels and short stories. We’d be here twenty-four hours talking non-stop about all the ways to do it, and it would probably still all be mysterious and head-scratchy.

That’s writing, isn’t it? Part mystery—how does the magic of pen to paper happen—how do we even describe this heavenly transcribing of thoughts? Part grind—no story is easy—requires sacrifice and time. Part skill—that’s a no brainer—you have to know your literary elements. Part determination to never give up—quitting is often the easiest part of writing—only, giving up gets you nowhere fast. Part, what you’re willing to do to improve—that’s a no-brainer—gotta get better. Part what tale you’re brave enough to tell—some folks really do fear criticism not just about the writing, but what the writing is about. And also, part whether or not you can check your ego at the door and kill all those darlings, those obstacles on your way to pursuing the strangeness of traditional publishing.

These are not easy things.

Today we’ll be talking about climate fiction and eco-horror. While the book I just turned in to my agent has little to do with this topic, the thriller I’m working on does, as do my first two novels, The Deading and Ten Sleep.

I’m very inspired by Charlotte McConaghy’s work, Migrations and Wild Dark Shore, as I am of Audrey Schulman’s Theory of Bastards, as well as various speculative fiction writers like Wagner, Vandermeer and Chronister. And oh, can’t forget Samantha Harvey’s recent Man Booker prize-winning novel Orbital. So lush and literary and idea-worthy about our fragile planet.

And nonfiction as well—I just finished Murderland by Caroline Fraser, Pulitzer-winning writer of Prairie Fire. Murderland is a mastercraft on what nightmare of our own making really means, connecting serial killers in the Pacific Northwest to corporations releasing untold amounts of lead and arsenic into wildlands, suburbs, and more.

I think over the next hour you’ll come to a conclusion. You’ll either head-scratch and say, No way I’m writing eco- and- climate fiction themes in my work, or you’ll still head-scratch then do a deep dive into today’s topic and find a dangerous realm filled with exciting characters and terrible real tragedies that reflect our very world right here on the central California coast.

Let’s start with some definitions, get a sense of where were going in this talk . . .

What is climate fiction? Fiction about climate change. That’s what it says on Wikipedia, anyway. Is generally speculative in nature, it says. Okay—not sure I completely agree with that—sounds like it was written by someone who doesn’t believe the science—and that’s the thing about this discussion—there’s a lot of disbelief going on in America. Be wary of those dismissing science. Doesn’t mean there isn’t room for debate. But we live in a society where huge swaths of America dismisses the starkest of tragedies, as if a deadly storm can’t steal away a child. Anyway, I like what the New York Public Library defines as climate fiction: “Climate fiction deals with the impact of climate change on the earth and on society. Spoiler: it’s never good!”

I also like this that they say:

“…might seem like a bummer to read given how close to reality some of it might feel, but it can be a compelling way to engage with issues that are fundamental to life on earth now and in the future. What’s certain is that this genre is growing as more authors, of both literary fiction and speculative and science fiction, are choosing to tell stories through the lens of a world dramatically altered by changes to earth’s climate.”

And I think we can add industrial disaster to this too, especially the kind that really take its toll on lands and people. And we have to take this a step further by saying climate fiction is a nightmare-of-our-own making kind of literature. It can be dystopian, and is always filled with dread—sort of a built-in conflict, right? And if done well, will hit you right in the gut, make you care about nature, make you care about the decline of wilderness globally, or the polluting of your creeks and wetlands, your bays and agricultural lands, locally. And as a genre, it can be wrapped in all kinds of other genres: horror, sci-fi, fantasy, thriller.

So what is eco-horror?

By its very nature it is blended genre, which is what a lot of speculative fiction does, taking two or more genres and smashes them together. The Deading includes horror, Climate fiction, Chicano fiction, and is a family story, a community story—it is experimental fiction as much as it is part fantasy too. Ten Sleep is part western, part eco-horror, part gothic, part Chicano fiction, part thriller.

Before we fine-tune our definition of eco-horror, let’s first define horror.

“Horror” is a scary word for some folks. Can’t tell you how many times I have to defend the genre. It gets exhausting. Someone says, “Oh I can’t read that, it’s too scary.” Well what literature isn’t scary? When the girls drop their doll into a basement at the beginning of Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, the first book in her Neopolitan series, as a reader, I’m terrified. What lurks in that dark, grimy place? Yikes. Guess what? Elena Ferrante’s work is simply great literature. It isn’t horror. It’s a tale of estranged friends in Naples, Italy. And like a lot of novels, it scares me at times.

Horror, however, is the literature of fear, and if done well, holds a dark mirror to society, and says, This is you. Horror is also a safe space to be scared—it is the thrill ride you’re looking for. Ever stand near the edge of a cliff? One false move and you’re dead from vertigo—that’s me anyway. We can’t just fly off. Our wings won’t work and we’ll plummet. But get on a rollercoaster and it’s the same thing as if going over that cliff—you go up and over time and again. You trust the technology to keep you safe. It’s a safe space that your fears occupy.

And that’s horror—a safe space that your fears occupy.

No monster is going to get you. And no ghoul is going to pull you into the earth. I find the doll in the basement far more terrifying than most horror.

We could break horror into two basic camps, though there are many, as well as many sub-genres and genre-blending styles. Anyway, there is pulp, and there is literary horror. I write the literary style. That’s why the animal chapters in Ten Sleep are inspired by the turtle chapter in John Steinbeck, and not by my latest viewing of Cujo.

So, now that we know what horror is, and can be, what is eco-horror?

Definition: If horror is the literature of fear, then eco-horror is perhaps the literature of man reckoning with the terrible things he’s done to the natural world.

So, could be an arsonist tale, could be an insane murderer of eagles. Oh, wait, that happened in real life. Did you read that news? A Virginia duck hunter angry at eagles and raptors, starts shooting and poisoning them. Kills over twenty. Gets a day in jail. The raptors were eating the ducks he wanted to hunt and kill. Yep—horror.

Now, eco-horror has been good to me. I once gambled on it becoming big. I wrote The Deading, and it paid off. I’m going to double down and predict again that climate fiction and eco-horror will be in even higher demand in the near future. Maybe already is.

Do I have proof of this?

No. And yes.

I say no in order to protect myself in case I’m wrong. But I don’t think I’m wrong. Let me explain . . .

Around 2022 or thereabouts, I was sitting in an audience in a Palm Desert hotel conference room, listening to one of those “what is the state of publishing” talks. Blah blah blah. An editor from Soho Press was being interviewed by UC Riverside Palm Desert MFA Director Tod Goldberg about what’s hot in fiction—you know, what do editors want to acquire? When the editor suddenly said, “climate fiction,” she had my attention. Then the director pointed at me. He might have winked and smiled. I just nodded—I was onto something.

It was that scrying mirror, right, that crystal ball I had gazed into before I started writing The Deading in 2019. Though I got sidetracked and dusted it off in graduate school. I was on to something. That led to me also writing Ten Sleep, a novel that also includes some of the same eco-horror themes.

Eco-horror and climate fiction are still sellable genres right now. McConaghy’s Wild Dark Shore instantly shot to the best seller lists this year in both the U.S. and Australia. So how can I say they will be even more sellable? Why would I double down?

For one, we as a society have a responsibility to our natural world that’s greater than even a few weeks ago. Look, writers are troops on the front lines of both thought and theory. Our works are more often political than not. Don’t let anyone tell you novels can’t be political in nature. The best ones are. Writers are supposed to be the kind of people unafraid to talk about the hard stuff. Reality check, we’re usually still afraid. We just do it anyway.

There is a moral and ethical responsibility when the time is nigh to talk about the hard stuff—I mean, we writers are the gauge checkers deep amid the boilers in the bowels of human existence—we have our fingers on the pulse—or are supposed to. And so we’re the appointed ones to weave these kinds of difficult conversations into our literature.

When the U.S. government recently decided to wipe federal websites of key evidence of climate change a week or so ago, that meant moral and ethical responsibility fell onto society itself. Same with the government having granted far too much power to corporations and killing the EPA. Be prepared for Murderland all over again, people. The government will soon be increasing their blame people of color and drugs for crime. They will ignore what corporations dump into the air, soil, lakes and rivers.

That means, those who create art, those willing to sharpen their pen-swords, or their two-hundred-million-dollar film budgets, need to step up. Yeah, that means Hollywood too. See what I’m getting at? If both are linked, then the right eco-horror or eco-thriller could see its film rights sold. That’s what happened with McConaghy’s Migrations.

What’s that recent article in The Atlantic? Had an interesting sub-heading: “If TV can change Americans’ views on gay marriage, why not the environment?” I agree. Why not have characters with climate-related backstories? Why not infiltrate the industry with “climate knowledge?” When is it ever time for an industry based on the arts to tell more of the real story of what’s happening regarding nature and the climate? Now. Now is the time.

And even if Hollywood continues to be slow to move on this, I believe more and more books will capture these themes.

And remember, publishers have their own agendas. They do know their roles in society, to be controversial, to show an ethical responsibility to race, ethnicity, history, climate, nature, etc. We are their voices, saying the hard things they also believe in—the hard truths about climate and corporate destruction that politicians and anti-intellectuals rattle their sabers at. Remember, books are intellectual, the naysayers say that reading books and news doesn’t matter, are a waste of time, or are flat-out wrong. They might even say, “Just go to church” (this lecture was presented in a church building).

And if publishers have a moral and ethical responsibility to tell the truth about climate change and industrial disaster, then what stories are they going to want to publish? Stories like The Deading, Ten Sleep, Wild Dark Shore… Murderland…

I took a chance with The Deading to tell a localized tale that begins in a fictitious version of Morro Bay and Baywood. Literally, close to novel’s beginning, an oyster farm is stealing nutrients from the ecosystem. It’s run by a ruthless capitalist named Bernhard Vestinos. And he will stop at nothing to expand his shellfish empire, even if that means sacrificing his marriage and the lives of his undocumented workers.

While a graduate student, a mere weeks after I finished a draft of the book, it sold. And then a year later, Ten Sleep was acquired by the same Erewhon Books editor, Diana Pho, formerly of Tor.

What I’m writing now is an eco-thriller. Remember, I’m doubling down. That means I’m banking that eco-thrillers are going to be hot commodities with editors. Part of the magic of the crystal ball, whether something like eco-horror or an eco-thriller will be a hot commodity, is really just me trying to stay on the curve, on the front of the wave of what editors might want.

But here’s some of my thinking on this:

Take Australian eco-thriller writer McConaghy for instance, who in America is writing the same kind of book? That’s tough. Not sure. I may not be reading widely enough to have found that person. Or maybe eco-thriller writers are few while the demand may possibly be high. And also, I know something else, to write them, you have to have attain a certain knowledge about climate change, thrillers, eco-horror, etc., and you have to have a focus on research, a combination of reading and being out in the field.

One of McConaghy’s works focuses the last of a bird species. In another, a seed vault is in danger of dying. So let’s talk birds. They’re tough to learn if you want to get them right. Birds take study, field research, understanding field marks, behaviors . . .

We should want to get animals right in our literature. Birds and animals are often characters in mine, and I have a lot of bird studies under my belt—every day for six-ish years. Hours on end. Can’t tell you how many times writers use the word “crane” when they likely mean egret. Or someone drops a sparrow into their narrative when why not tell me what kind? Anyway, this is my way to say that maybe I’m qualified. Not to be the American McConaghy, but to just be myself, a dual ethnic writer in America with some expertise about North American birds and who cares about the ravages of climate change and industrial disaster on our wildlands and urban riparian spaces.

So, why else double down on climate fiction being hotter than ever?

What do we have so far to account for this doubling down? We have an Australian being a popular climate fiction author this year, which is a big indicator that the genre is hot. We have social and ethical responsibility because the U.S. government has attacked climate change and the environment by erasing information and resources from their websites, etc. And we have another thing—the environment itself.

What have the headlines been over the past week?

Texas floods. Maybe a hundred-year storm. Maybe not. Either way, we’ve been riveted by Texas’s climate-driven crisis, which has destroyed the lives of many families. Jane and I lived close to those areas when she was in graduate school. The very day we were moving back to California, a catastrophic deluge fell on our area. We could see helicopter rescues. Friends’ apartments were flooded, as was the San Marcos fire department. Entire fire engines submerged. A house in Wimberley literally washed into a river. The family inside perished.

Writer Rebecca Solnit said a few days after the recent devastating Texas flood, “This climate catastrophe coming on the US’s independence day is a reminder that we were never independent of nature and never will be, and that there is a terrible cost to undermining its elegant systems.”

She goes on to quote Bill McGuire, Professor Emeritus of Geophysical & Climate Hazards, University College London:

“The tragic events in Texas are exactly what we would expect in our hotter, climate-changed, world. There has been an explosion in extreme weather in recent years, including more devastating flash floods caused by slow-moving, wetter, storms, that dump exceptional amounts of rain over small areas across a short time. This frequently overwhelms river catchments leading to severe damage to adjacent infrastructure and loss of life. Such events will only become more commonplace as the global temperature continues to climb, driven by carbon dioxide emissions that still top 40 billion tonnes every year.”

Solnit and McGuire read like characters in a novel on climate change, or scientists in an eco-horror speaking out—I mean, this is the stuff of science fiction, of eco-horror, that predicts the very monsters that might consume us in our dreams.

While writing The Deading, which is part science fiction as well as eco-horror, I literally stole a quote from a friend’s Facebook account, with approval from the ornithologist who wrote the words. He studies not only birds globally, but ocean weather, ocean temps, and climate change. Read on:

I know it seems like an obsession with water temperature, but this is pretty unusual and perhaps to the land-based, it needs the context. We do get warm water offshore around this time in an average year. What is different this time is that the warm water has entirely displaced the colder inshore water. Our charts usually show yellow and orange offshore (warm) and blue/green inshore (cool). But now it is beyond orange into the brown (68°F) in some areas, and no cool water at all inshore. This is unusual in two respects: 1) the warm

water has lapped up right to shore; and 2) the warm water is several degrees F higher than what we usually consider warm around here. This is very warm for us. Note that an unexpected Least Storm-Petrel was netted on Southeast Farallon Island last week. That suggests a marine heat wave, rather than El Niño, but as the latter strengthens and warm water shows up from the south, the entire situation will unite. The current sea surface temperature anomaly map shows a cold region to the south of us, separating us from the El Niño. It

interesting if at the same time troubling. I guess as we fry on this earth, we will be happy enough seeing all the bird vagrants brought in by the doomsday scenario. Fascinating but terrible. This will mean gigantic red tides and demonic acid outbreaks. Say goodbye to crab season and expect more mass bird die-offs.

And then we get thoughts from that awful oyster farmer Bernhard in The Deading:

He admits what could happen if there was a danger. A decrease in micronutrients means less meat per shellfish. A decrease in customer satisfaction. He can’t expand his oyster farm if meat quality heads to the toilet. Some of his fishing friends predicted this would happen. Thank god these marine heatwaves go underreported. He bites his tongue. Dr. Magaña. She has it out for him, he thinks, for oyster farmers in general, has for a while now. He doesn’t believe he’s destroying habitats, no way, not for a minute. It can’t be what she thinks. Plenty of tidewater nutrients to go around.

The knowledge alone, once you dive in about ocean warming will make you feel dread, like this line in The Deading, pulled partly from scientific documents on climate change. It’s Dr. Magaña warning Bernhard:

The (ocean) Blob is a result of unseen explosions like the atom bombing of Hiroshima, transforming the seas with 228 sextillion joules of heat. No doubt ocean food chains are affected. Fish numbers in Pacific coastline estuaries are already down. Salinity is up What you can do: Harvest shellfish and plant crops early. Monitor for predators. Consider other methods of growing over the next few years. Consider more protection from tides. Consider what might happen if the worst comes. No one can predict how bad this will be.

Yeah. Dread . . .

In Ten Sleep, I use a few literary methods to craft eco-disaster and dread, including narrative, sensory detail, epistolary techniques, and dialogue. I take scientific knowledge pulled from journals and news stories and weave thoughts about the bentonite mining responsible for nasty pits that scar the earth. Ten Sleep’s characters are on a cattle drive through these lands, and Greta, the main character, in one flashback recalls her conversations with a retired professor who warned her about such eco-dangers. You can say Greta is learning—she’s trying to understand a lot of things about her messed up life . . .

Anyway, here you can see how I craft climate fiction in Ten Sleep with sensory detail and scientific knowledge, meshing with both eco-horror and western tropes.

By late afternoon a smell came to the rolling prairie that disturbed Greta’s sinuses, making her sneeze and develop a slight cough. This wasn’t cowshit or stagnant pond water wrinkling her nose, but sulfur blowing from the open-air bentonite mines outside of Ten Sleep and Hyattville, a stink that sometimes wafted across dozens of square miles within Bighorn Basin.

Open quarries from bentonite surface mines, Greta knew, could be found far downslope, west of the trail and prairieland they’d navigated, accessed by private roads owned by a single mining company. Thanks to discussions with J.A. Maynard and an illuminating study and investigative report that he shared, Greta knew more about these pits where absorbent clay crystals were extracted. It was about far more than just seeing piles of yellow-and-green machinery dissecting the landscape into an ugly brown mass. She learned that the area had been saturated with volcanic ash from ancient geologic activity over in Yellowstone. While the area had last seen rhyolitic lava flows as recently as seventy thousand years ago in the Pitchstone Plateau, there had also been caldera-forming eruptions 631,000 years ago, and dozens of eruptions since, not to mention three massive explosions over a little more than two million years.

Turbulent eras upheaved entire mountains of pyroclastic material into ash clouds, including one 173,000 years ago that resulted in a collapsed caldera forming the western end of Yellowstone Lake. Those immense clouds from the three gargantuan eruptions poured over much of the western half of North America, mostly southeastward, and settled on an ancient seabed that had become the entire Bighorn Basin, though ash had blown as far southwest as Mexico, and southeast as far as Louisiana, where it lay upwards of three feet deep. Those ash layers eventually became part of a sedimentary geologic process that formed the absorbent clay known as bentonite. Most Wyoming folk, Greta too, called the clay gumbo, but only after it came in contact with water, expanding interconnected clay crystals to more than fourteen times the size of their dry mass. Contact with the sticky and hazardous mud could make moving the herd near impossible. Their trail wound far from any massive deposits, though small gumbo patches appeared, which were slick, sticky and waxy, and for a short while trapped two of the calves.

Maynard brought the bentonite mining problem to Greta’s attention one evening while they talked out on his front porch. He poured beers, shared some big helpings of elk steak, asparagus, and mashed potatoes, having invited her to share supper after seeing her poke around for his latest contributions to the little library box. She’d pulled out another book on geologic processes in Bighorn country.

“Those sons of bitches act like there’s no environmental impact,” he said about the mining company, “but everyone knows that around Ten Sleep over in Washakie County, grouse habitats and big game wintering areas get screwed over by the company. On top of that, they sell most of their clay to cat litter companies.”

Greta had seen plenty of open mine pits, warehouses, and processing plants, not to mention endless convoys carrying the minerals down highways. Maynard told her that one bentonite plant had a huge sign tacked to its processing plant for everyone to see: AS REGULATIONS GROW . . . FREEDOMS DIE. He called it “the usual corporate bullshit vying for complete control of environments they don’t care about ruining.”

“But it’s just clay,” Greta countered, chewing a piece of steak. She didn’t think it was her fight and he picked up on that.

“You should care,” he said. “Ecosystems are dependent on plants, geology, weather, animals. This stuff isn’t made up for textbooks just so kids can say oooh to nature. Ecosystems are more fragile than ever. They’ve been encroached on, destroyed. Lax enforcement of regulations in bentonite mining means lack of proper oversight, rules violations, and that translates to more environmental harm. Aren’t the particulates and gasses bad enough? Who wants to smell sulfur? Who wants to get asthma from this garbage? It’s a regulatory mess, Greta. The Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality needs to do what’s right, enforce laws, train their inspectors to take note, and not let these companies mine year-round, or be lazy in how the land gets reclaimed once they’re done ravaging it.”

Much of Ten Sleep is about man’s pact with nature in the form of Mother Canyon and the abuse of that pact over time. Eco-horror also comes through a series of interstitial chapters about animals, from their POVs. We get chapters about a coyote, sparrows, a bear, an ancient owl, prairie dogs, a jackrabbit. Why? Because they’re part of nature, they’re what’s at stake too when we have climate change and industrial catastrophes. And dare I say, war? In the wars in Ukraine and Gaza we forget that there are plants, and animals, and insects. We forget about the destruction of biodiversity, or what happens to sea life when a Russian ship sinks and burns. We get so hyper-focused on the human element and the possible re-writing of invisible landscape boundaries, that we forget about the flora and fauna.

While none of the missing, dead, or survivors of the recent Texas floods are characters in our stories, they are symbolic of the tales we could write. The miraculous survivor washed downstream fifteen miles. The hero Coast Guard rescuer who saved 165 souls. The team from Acuna, Mexico making dangerous water rescues, though America won’t rescue Mexican immigrants. A child found floating on a mattress. A mother and son wrapping themselves around a tree while riverwater and killer detritus rush around them. A father who dies just wanting to break a window and get out, who says while he’s departing this world, I love you. I’m sorry.

It’s this human connection amid climate crisis and industrial disaster that drives climate fiction, eco-horror, and eco-thrillers. Who these people are, are everything to our stories—it becomes easy to channel characters similar to them—because they are us. And the deeper we dive into who they are, and who we are, the more is at stake when peril comes, whether a monstrous storm, some dino-monster, or a serial killer crawling from the toxic sludge that corporations dumped outside Tacoma in the 1970s.

Novelists have the power of storytelling on our side. We have the power to up the stakes. And stakes are everything.

But in real life? We easily forget or deny. We become no better than the politician or corporate stooge. Bernhard in The Deading reminds us he’s a true capitalist, reminds us that we tend to dismiss the stakes when politics and capitalism get involved. That’s why Bernhard is in the story. He’s more a part of us than we might readily admit.

When we see choices on the page from characters like Bernhard, we know what they’re made of. When he sees genetically modified Atlantic driller snails invade his precious oyster farm, he makes his choice about one of his workers. She sinks into the abyss because of his corporate wisdom.

Bernhard, sadly, is so many of us during both climate and industrial crises. Too few of us are the hero from the Coast Guard. Too many of us quickly ignore tragedy. We get caught up in the political aftermath. We start paying more attention to Ted Cruz lying about rushing back from his European vacation to tend to his flock. We glue to the Georgia politician screaming that Texas floods are a lie. We forget the storm, the rescues, the images, the children washed away from their lovely riverside summer camp. They become figments of our imagination.

It’s this weird thinking we Americans do about all kinds of dangers: why on earth would we criticize the pesticides sprayed in our homes and around our yards? We want to keep our homes free of weeds and spiders, don’t we? At what price to ourselves and animals? How about the many pesticides on our fresh fruits and veggies. Our smelters, we used to say, those are fine—lead and arsenic and cadmium won’t do anything to us—until you read Murderland. The solar wind farm we’re building off the Central California coast is for all of us! Everyone will be safe! Everyone will benefit from energy! And the ocean that’s currently hiding thousands of barrels of leaking DDT, etc. It’s fine too! The plastics inside you from years of drinking from Styrofoam cups. Fine. All fine!

No. It’s not fine.

I worked in a Styrofoam factory. I worked in a paperboard plant. I worked in a Fiberglas factory under a thousand-degree furnace, beneath ungodly mixes of chemicals. I pulled a piece of that glass from my hand twenty years later.

These are real horror stories.

Don’t be afraid of the genre. The genre is the safe space—the real world isn’t.

I once saw a man go insane in a paperboard factory. He was carted out on a stretcher. I’m now thinking it was the chemicals that got into his brain. I remember, I was barely making ends meet, the half-billion-dollar Forest Products Corporation was raking in millions. Though an avid naturalist and birdwatcher now, back then I stupidly had no sense of climate change, of deforestation, of illegal timber cutting operations, the loss of habitats, the dwindling of species, and how my employment supported such operations. I also didn’t know how the parent company, Manville Corporation had also been parent company to Johns-Manville Corporation, the world’s largest producer of asbestos. By 1981, around 400 asbestos-related lawsuits were being filed per month. In 1982, Manville and its subsidiaries, filed for bankruptcy. They had been found liable for “personal injuries and illnesses arising out of the asbestos operations of Johns-Manville.” Financial liabilities added to “between $2 billion and many times that amount.” The bankruptcy allowed them to reorganize as Forest Products “serving as one of five wholly separate operating subsidiaries,” amid other corporate reorganizations, where they argued they were “improperly prejudiced by the entanglement of their financially sound debtor with the besieged asbestos maker.” And then I started working for them . . .

Oh the monsters in Murderland, and the monsters we can all write, putting the funhouse mirror up to the corporations . . .

Reminds me of the 1984 Bhopal disaster—has anyone written an eco-horror about that? An essay written thirty-four years after the event in 2018 has a heading that describes it all: “The World’s Worst Industrial Disaster Is Still Unfolding.”

An excerpt:

In old Bhopal, not far from the small Indian city’s glitzy new shops and gorgeous lakes, is the abandoned Union Carbide factory. Here, in one ramshackle building, are hundreds of broken brown bottles crusted with the white residue of unknown chemicals. Below the corroding skeleton of another, drops of mercury glitter in the sun. In the far corner of the site is the company’s toxic-waste dump, shrouded in a sickly green moss. Not 15 feet away, a scrawny boy of about 6 tries to join a game of cricket. A few skinny cows graze next to a large, murky puddle. Strewn on the ground are torn plastic bags, yellowed newspapers, stained paper cups. And in the air, the pungent fumes of chlorinated hydrocarbons.

On December 3, 1984, 40 tons of a toxic gas spewed from the factory and scorched the throats, eyes, and lives of thousands of people outside these walls. It was—still is—the world’s deadliest industrial disaster. For a brief time, the Bhopal gas tragedy, as it became known, raised urgent questions about how multinational companies and governments should respond when the unthinkable happens. But it didn’t take long for the world’s attention to shift, beginning with the Chernobyl nuclear accident a little more than a year later.

Five hundred thousand people were injured. Thousands died. No one has cleaned up the land. Thanks Dow-DuPont.

And so we look the other way, search for other explanations. We look to the corporate-bought politicians, the corporate-paid scientists, the corporate-paid doctors, and we believe them. It’s easy. Just nod along with them.

It’s like Bernhard from The Deading, or like Tiller from Ten Sleep.

Loved one dying of cancer who lived by industrial pollution? You don’t need to know what was in the soil, just like you don’t need to know what was in the paint. Monarch butterflies almost dying off? Common Murre mass die-offs. The current gray whale die-offs. Can’t tell you how many whale carcasses I’ve seen on my beach walks up and down the central coast. Or when I’m birdwatching along creeks how many homeless are living in them, piling metals along the shores, doing things I don’t want to even know about. The wastewater plant pouring in more waste—yikes. Wastes from agricultural toxins. From cars and streets. What I do know is we have one of the most polluted creeks and beaches in California right here in San Luis Obispo County. Not too proud of that. People splash through the creek mouth when it reaches the ocean. They surf. They paddleboard. They let their dogs run and play in it. They lounge in the sand saturated in toxins.

The cold, stark reality? We need to write stories where our characters and worlds are living in a nightmare of our their own making.

And it doesn’t matter if it’s speculative fiction or not. It doesn’t matter if it’s a tale of the past, present, or the future. What matters is that these stories are told.

A reader should want to know something, should want to solve a mystery when they read. We want them to turn the page. So we should want them, like our characters, to desperately seek answers about climate and industrial disasters. We should write stories where we wonder what is at stake with both characters and the land, a dying land, a poisoned land, because that usually means—a poisoned people.

Please take a moment and purchase Ten Sleep and The Deading. Read more on nicholasbelardes.com